The Museum Space and Ethics of Imperialism: The Parthenon Marbles

By Abby Baytieh

Art by Julia Wong

Thousands of years ago in Athens, a temple was built.

With a team of sculptors and architects, the statesman Perikles outfitted the Acropolis rock with a complex of divine monuments in the 5th century BCE.1 The center of this: the Parthenon.

Dedicated to the godly patron of the city, Athena, the temple was an architectural marvel. Wide Doric columns curved and bowed like the trunks of great trees, supporting interior and exterior friezes lined with scenes of battle and celebration alike. Within, a gilded statue of Athena Parthenos stood regally, towering over those who came to worship her.2 Most notably, shining in the sun within pointed pediments, two series of thoughtfully-sculpted figures depicted striking mythological scenes. In the east pediment, an armored Athena was born fully-grown from the mind of Zeus. In the west, the story of the city of Athens was told – a contest between Athena and Poseidon to determine who would win Attica, the city renamed Athens after the goddess’s success. In all, fifty statues carved from Pentelic marble were adorned with bright paint and flashy metal accessories3 to reside within the upper sections of the Parthenon.4 It was not just a monument to the gods, but a monument to the city itself – a testament to victory and to a revitalized sense of shared community. Built after an extraordinary triumph against the Persians in the 5th century BCE,5 it was a reassertion of Athenian identity.

But just as ancient Athenian society could not last forever, neither could the splendor of this Acropolis. The annals of time saw the rise and fall of empires and rulers, and though the temple never lost its regality, the status it once held as symbol of Ancient Greek religious practice shifted as the hands that controlled Athens changed. In 529 CE, it was converted into a Christian church by the Romans. In 1205 CE, the Franks turned it into a fortress. In 1458 CE, the Ottoman Turks turned it into a mosque. Yet, the structures of the Acropolis suffered no significant damage until a fateful September in 1687, when war with the Venetians turned catastrophic, and a mortar shell exploded the stored gunpowder in the Parthenon, turning the monument into a shell of what it once was.6 It was in this state that the British would find particular interest in the monuments of Ancient Greece. Enter: Lord Elgin.

Fascinated with Grecian art, Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, derailed his trip as a British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire to go to Athens. Once there, he spent considerable funds for artists to draw the monuments, but his interest in the pieces escalated into a desire to claim them. In 1801, he received a firman – a royal decree – from the Ottoman Sublime Porte that allowed him to “‘fix [the] scaffolding round the antient Temple… to mould the sculpture and visible figures… in plaster… [and] to take away any pieces of stone with old inscriptions or figures [not a part of the original monument, but added in its later uses]”.7 It was clearly intended to be a restoration project; in no part of this decree was Elgin allowed to remove the marbles themselves. Yet, permission to interact with the marbles was enough, and, arguing that their deteriorating condition was at stake while under Turkish hands, he felt “induced to undertake [their removal]”.8 Over the next eleven years, Elgin would undergo an immense effort to bring the marbles back to Great Britain,9 one that saw the buildings of the Acropolis damaged10 and the marbles temporarily shipwrecked.11 Once back on British soil, Elgin displayed the marbles at his estate until, bankrupted from transporting the artifacts, he sold them to the British Museum in July of 1816 through an Act of Parliament:12

That on Payment of the said Sum of Thirty five thousand Pounds,13 the said Collection shall be vested in the Trustees for the time being of the said British Museum, and their Successors, in perpetuity… and [be] called by the Name of The Elgin Marbles.14

Thus, in one fell swoop, not only had Elgin gained a small fortune, but he had also ensured that the marbles would remain within British hands forever.

From the British Museum’s inception, the laws that governed it are the very things that have allowed it to become so entrenched in infamy. In 1753, the British Museum was founded on the collection of one Sir Hans Sloane,15 and it was intended to be a grand project:16 a national public institution that would be free for all to enjoy.17 Crucially, because the British Museum is a public institution, its power – and therefore its possessions – fall under public ownership, theoretically belonging to the whole of the British people. The way Parliament articulated this ownership in 1753, and then again in 1878,18 asserted that, because the contents of the British Museum were under public ownership, the Trustees of the British Museum could only remove acquired artifacts should they be duplicates, but almost anything acquired by the Museum stayed within its collection:

[The] several collections, additions, and libraries so received into the general said repository [the Museum’s collection] should remain and be preserved therein for public use to all posterity.19

The Trustees could not sell objects or otherwise remove them from the collection, for that collection belonged to the public. Conveniently, this ruling has been used to skirt responsibility for looted objects even now: the Museum is just “following the law”. Even though 99 percent of the 8 million objects owned by the British Museum are not on display,20 they are legally required to remain under British Museum ownership.21

Changes to this law have been minimal,22 and the most recent British Museum Act passed in 1963 upholds this precedent. The Act states that the Trustees of the British Museum have the authority to sell, exchange, or give away an item at their discretion if it is a duplicate, if it was created after 1850, or if it is “unfit to be retained in the collections of the Museum and can be disposed of without detriment to the interests of students”.23 Though such provisions theoretically allow for objects in the collection to be deaccessioned, the policy itself is too vague to be used in practice and can easily be countered by an assumption of student interest. Because there is no force within the Act that necessitates deaccession, it essentially allows for operations to continue as usual.

Since 1963, only very specific legislation has been passed that allows for the return of art objects: the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act in 2009.24 As early as 1938, Nazi confiscations of artwork began all over Europe.25 It is estimated that over five million objects were stolen by the Nazis over the course of the war,26 and while many were sent into private Nazi collections, a considerable amount of looted artworks were sold to finance the Nazi war machine.27 Using channels that ran through Switzerland and Paris, looted art exchanged hands and entered into global circulation, where it could be further bought and sold – and distanced from its rightful owners. When the Allied forces learned of such confiscations in early 1943, they became determined to protect and recover art from across war-torn Europe and established specific commissions that operated even after the war was over. Yet, despite the fact that the Allies knew of Nazi confiscations, the damage had been done. With art objects scattered into the global art market, the process of restitution became tricky: over time, looted artwork would only become deeper entrenched in global circulation. Thus, efforts to locate and return pieces looted by the Nazis are still active, such that a majority of current restitution efforts focus on Nazi-era objects. With the development of the internet and the declassification of records over time, the 1990s and 2000s saw a new wave of attention for Nazi-era restitution,28 so much so that there was wide-scale public pressure for institutions to reexamine their collections. In 2009, British Parliament passed the Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act, which encompasses not just the British Museum, but a breadth of British institutions. It states that a Nazi-era item (1933-1945) may be transferred out of a collection should it receive a recommendation from an Advisory Panel, and then approval from the Secretary of State.29 While this Act does not have enough breadth to affect the Parthenon Marbles, it is the closest the law has come to overturning the British Museum Act – the very thing that keeps the marbles in British possession.

While the British have not been intent on the return of the Parthenon Marbles, the same cannot be said for Greece. Since they established independent statehood in 1835, the people of Greece have been petitioning to get the marbles back, even going so far as to attempt an official claim in 1983. But, as The New York Times documented at the time, this petition was rejected by the British Government, who did not consider the request to be formal enough.30 Yet, despite such rejections, Greece has continuously developed efforts to bring the Parthenon Marbles home. When arguments were made that there was no governing force to oversee the maintenance of the marbles, the Acropolis Museum was founded in 1865, followed by the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments in 1975.31 When arguments were then made that there was no sufficient place to store the marbles, the Acropolis Museum developed a larger building on the south side of the Acropolis rock to accommodate them in 2009.32 Outfitted with three main levels and 14,000 square meters of exhibition space,33 the Acropolis Museum was designed to restore, care for, and display the various architectural elements and artifacts from the Acropolis rock, including even those that were no longer in Greece. However, despite these monumental efforts, not one marble has been returned.

The most recent public update from Parliament on the Parthenon Marbles occurred in December 2023, during a short debate on the disputed ownership. While they addressed the claims to the statues made by Greece, and many members of Parliament asserted that the statues could be returned as a gift, the entire debate concluded by validating the belief that the British Museum itself owned them and that Parliament could do nothing but continue to uphold British Museum law.34 Discussions of a possible loan deal were also sprinkled throughout the debate, but since a loan would require Greece to concede that the British Museum has rightful ownership, even those at the debate noted that it was unlikely. Thus, the “Elgin Marbles” Parliamentary debate did nothing but reinforce British ownership.

Indeed, time and time again, the British Museum only continues to maintain their claim to the statues. Above all, this claim currently depends on the firm belief that the British Museum serves as a singular, crucial hub of global culture: not only is it best to display the statues there, but such a display rightfully conveys the statues’s significance to history. As the British Museum’s webpage for the Parthenon Sculptures claims:

The collection is a unique resource to explore the richness, diversity and complexity of all human history, our shared humanity. The strength of the collection is its breadth and depth which allows millions of visitors an understanding of the cultures of the world and how they interconnect… The Parthenon Sculptures are an integral part of that story.35

Yet, an examination of the curatorial strategies within both the British Museum and the Acropolis Museum highlights how this concept of the British Museum as a uniquely suited world museum could not be more wrong.

Entering into Gallery 18 of the British Museum – the Parthenon Room – the walls appear most striking: pale, muted stone spans their entirety, save for the sections of frieze aligned in a band around the room. Elements of the Parthenon’s architecture are imitated through tall columns on either end, where both ends of this long passage open up into smaller rooms, each containing the pedimental sculptures facing in. Lined up on a display of similar stone, the fragments are spaced out as they would have appeared positioned within the pediment. Thus, from the very center of the room, a viewer can see all the marbles oriented towards them. That is what is most telling about the curation of the Parthenon Room: the exhibition is directed inward. Because of the very nature of the exhibition, the viewer enters a space in which the marbles are enclosed. This mirrors the very ideology of the British Museum. Similar to how the institution contains the marbles within its collection, they are contained within its very walls: trapped in a room that centers the viewer, the owner.

The Acropolis Museum is very different: its curatorial approach displays a different ideology. Visitors to the Acropolis museum will first and foremost notice a lot more windows present within the building, allowing for more light and offering a view of Athens. With multiple floors all dedicated to the same subject – the Acropolis – the Museum provides a wider breadth of knowledge and space, one that allows viewers to better take in and understand the artifacts on display. This is most prevalent on the upper floor, the one dedicated to the Parthenon. Strikingly, instead of orienting the exhibition inwards, it is directed outwards. Visitors walk out of a central room explaining details of the Parthenon and its restoration to find sections of the frieze lining the outside of that central room. Turning the corner reveals the pedimental sculptures opened towards not only the viewer, but also the wide windows spanning the whole upper floor. Remarkably, through those windows, one is even able to see the original Parthenon. While most of the sculptures are casts of the stolen originals, they are on display and are viewed in the direction one visiting the original complex would have been viewing them. Altogether, this curatorial display does the exact opposite of the British Museum. Instead of centering the viewer, the artifacts themselves are centered. Curatorially, they are not trapping culture in, but sharing it openly, in a way that respects the intention of the original monuments.

Intentionality is indeed the heart of the Acropolis Museum’s curatorial choices. Beyond the statues of the Parthenon, the display of another monument from the Acropolis – the Erechtheion – demonstrates how the museum strives to protect all its statues, even those held within other institutions. A temple complex that was dedicated to a variety of deities, 36 the Erechtheion’s most recognizable feature is its south porch, the roof of which is supported by six κοραι statues: statues of women with ornately draped robes and long hair, who serve as columns. Named the Καρυάτιδες, or the Caryatids, these maiden statues have gained worldwide renown. While five of them are currently housed within the Acropolis Museum’s walls, strategically brought indoors because outdoor conditions were weathering them too harshly, one of the statues remains within the British Museum. Finding this statue in the rooms of the British Museum is no easy task: she is hidden away behind other exhibits, tucked into a corner of the Museum’s massive layout. One has to search to find her. In comparison, the Caryatids displayed within the Acropolis Museum have a whole balcony reserved for documenting their conservation and presenting them to the public. Oriented in a rectangular pattern similar to the temple’s construction, the five Caryatids stand together, but importantly, a space is left vacant front and center for their missing sister. With her pointed absence, the Acropolis Museum truly demonstrates the breadth of this loss. Not only does her presence in the British Museum make the temple reconstruction incomplete, but her absence is felt almost as a form of grief: there is no replacement, no plaster cast, which could rightfully fill her spot. The empty space reserved for this final Caryatid sends a message: Athens is waiting to welcome her home.

Unfortunately, regardless of how the Acropolis Museum’s display is more well-suited to illustrate how its monuments would have been perceived and appreciated, there is still so much work to be done in order to bring the marbles back to Greece. This is crucial work to do. It is not just about ownership; it is about the connection the marbles provide the Greeks to their own cultural history.

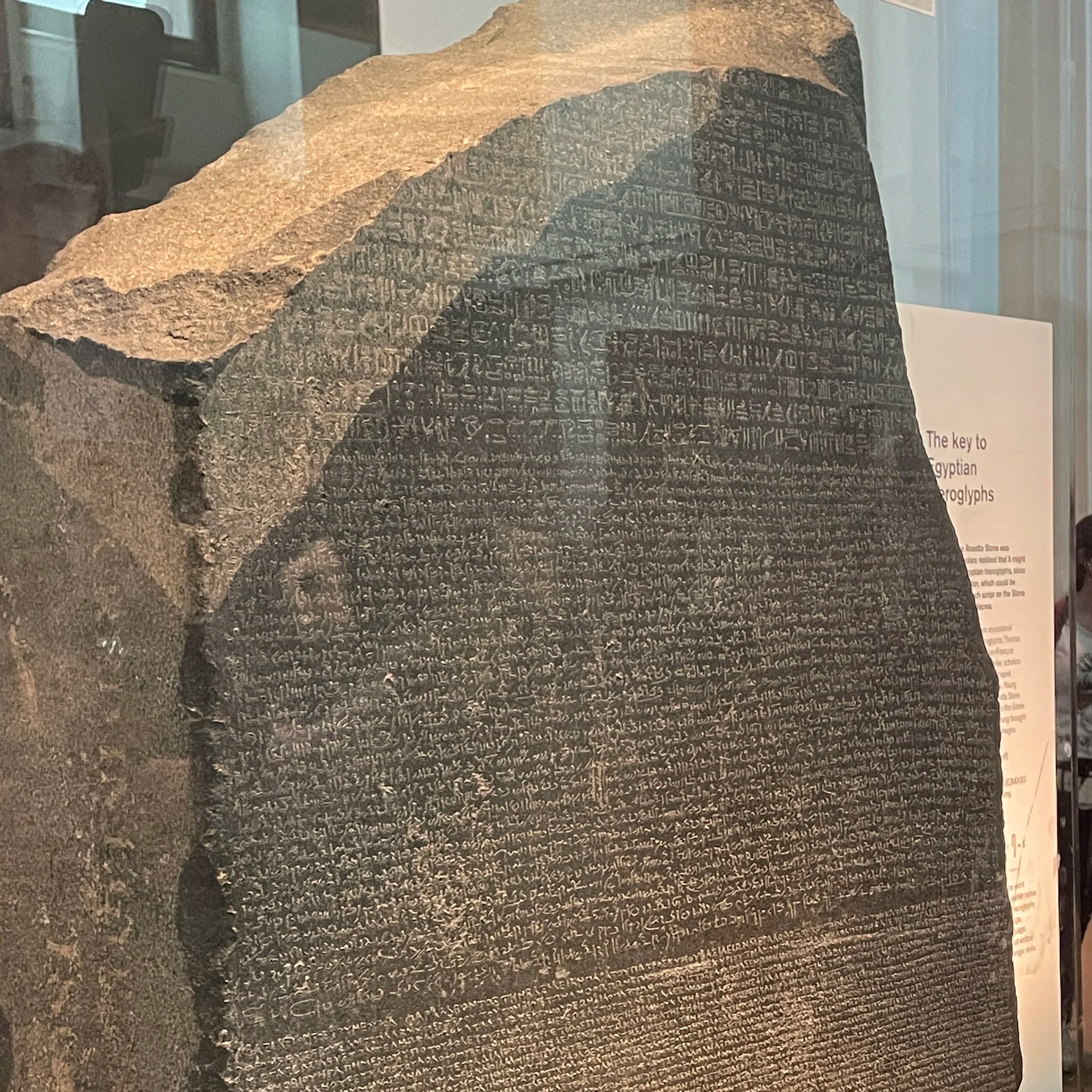

Still, despite how little overall progress has been made since the marbles were taken, the case of the Parthenon Marbles is only one of many. The Parthenon Marbles are so well-known because of how significantly Western cultures value “classical” studies. Ancient Greek and Roman culture already plays a role within public consciousness, and as such, it is no surprise that the monuments stolen from the most well-known Greek city-state get the most press. But within the British Museum’s collection, they are only one mere example of the objects stolen and kept through the mechanisms of imperialism. Take, for instance, Hoa Hakananai'a (and Moai Hava) from Rapa Nui. 37 These large statues are literally thought to be the ancestors of the people of Rapa Nui. Yet, they have been separated from their homeland for so long without hope of return that, in an effort to at least try to partially connect them to the land, a delegation brought earth from Rapa Nui to place underneath Hoa Hakananai'a. Or, for example, The Benin Bronzes from West Africa. 38 The bronzes once adorned the palace of the Kingdom of Benin and articulated their history. But when Europeans came and ripped them from the walls, they lost the order of the bronzes, meaning both the physical objects and the stories within them were taken from the people of Benin. Now, they are literally housed in the basement of the British Museum. Finally, consider the British Museum’s entire section devoted to Egyptology. From crowded mummies stripped away from the very words that provide them their afterlife, to the fact that the Narmer palette is displayed such that viewers have to look down at it, 39 the representation of Egyptian culture feels incredibly disconnected and disrespectful. Not to mention the Rosetta Stone: 40 having a piece that was so crucial in connecting modern society to that of the Ancient Egyptians within the British Museum's collection ignores its impact on the world today. All this considered, the Parthenon Marbles still remain the most well-known items of contention within the collection. While this press certainly isn’t bad and continues to garner support for their return, it is important to acknowledge that there are other cultural objects similarly being held captive, away from their countries of origin.

Repatriating the Parthenon Marbles is a crucial first step in examining the role of Western museums and their acquisitions, one that may eventually lead to the repatriation of a significant amount of their collections. The British Museum knows this (and so do other Western museums). That is why returning them is imperative: while a reexamination of Western museum practices might mean the end of the museum institution that we know today, it will foster the beginnings of a global culture more deeply connected to its roots through its ancestral artifacts.

UNESCO, “Acropolis, Athens.”

The British Museum, “An Introduction to the Parthenon and its Sculptures.”

Acropolis Museum, “The Pediments.”

Such painting and decoration that has been lost to time in one way or another was common for all the carved details in the Acropolis.

UNESCO, “Acropolis, Athens.”

Ancient-Greece.org, “History of the Acropolis.”

Stephen, Dictionary of National Biography, 130-131; “Old inscriptions and figures” here refers to additions from later uses of the Parthenon, described above.

Stephen, Dictionary of National Biography, 131.

By “marbles” here, I am referring to 56 sections of the frieze, 48 sections of the metopes, 19 figures from the pediments (all from the Parthenon), 1 of the Caryatids (the female statue that served as a column) from the Erechtheion, 4 frieze sections from the Temple of Athena Nike, and other assorted antiquities: Ancient Greece.org, “History of the Acropolis.”; Acropolis Museum, “Museum History.”

Ancient-Greece.org, “History of the Acropolis.”

Stephen, Dictionary of National Biography, 131.

In 1816, there was also a Committee within the House of Commons that was tasked with examining Elgin’s actions. As expected, they reaffirmed that the collection of marbles acquired by Elgin was done so fairly.

3,788,950.50 United States dollars today, which is actually quite cheap for the art market (ironically).

UK Parliament, British Museum Act 1816.

Sloane gained his collection through the wealth and global connections he created from his vast sugar plantations. The British Museum does openly recognize this history, but that is a fairly new development (~2020).

The British Museum, “History.”

At first, this meant only well-connected individuals who could get tickets for a tour.

UK Parliament, “British Museum Act 1878.”

UK Parliament, “British Museum Act 1878.”

Curiously, in 2023 a former curator was found to have stolen and damaged over 1,800 artifacts to sell them on eBay, which he was able to do partially because the catalogue of the 8 million objects in the collection is incomplete: The New York Times, “British Museum Sues.”

The British Museum, “Fact Sheet.”

For instance, in 1902 there was an Act which allowed Trustees to remove certain rarely-used print material and place it in a storage building in the Greater London Area, but this building was still owned by the British government: UK Parliament, “British Museum Act 1902.”

UK Parliament, “British Museum Act 1963.” Section 5.

In 2004, there was also legislation passed to allow for the return of human remains from the Museum collection, but that is a field distinct enough from art objects: UK Parliament, “Human Tissue Act 2004.” Section 47.

Rothfeld, “Nazi Looted Art.”

Gravenstein, “Lost Art and Lost Lives: Nazi Art Looting and Art Restitution.” 1.

Rothfeld, “Nazi Looted Art.”

Gravenstein, “Lost Art and Lost Lives: Nazi Art Looting and Art Restitution.” 1-2.

UK Parliament, “Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act 2009.” Section 3.

New York Times, “Greece to Ask Britain For the Elgin Marbles.”

Acropolis Museum, “Museum History.”

Acropolis Museum, “Museum History.”

Acropolis Museum, “The Museum Building.”

UK Parliament, “Elgin Marbles.”

The British Museum, “The Parthenon Sculptures.”

Acropolis Museum, “The Erechtheion.”

The British Museum, “Moai.”

The British Museum, “Benin Bronzes.”

Details the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt, kickstarting the very first Egyptian dynasty.

The British Museum, “Everything you ever wanted to know about the Rosetta Stone.”

Bibliography

The Acropolis Museum. “Museum History.” Published 2018. https://www.theacropolismuseum.gr/en/museum-history.

The Acropolis Museum. “The Erechtheion.” Thematic Section. Published 2018. https://www.theacropolismuseum.gr/en/other-monuments-periklean-building-programme/erechtheion.

The Acropolis Museum. “The Museum Building.” Published 2018. https://www.theacropolismuseum.gr/en/museum-building.

The Acropolis Museum. “The Pediments.” Thematic Section. Published 2018. https://www.theacropolismuseum.gr/en/sculptural-decoration/pediments.

Ancient Greece.org. “History of the Acropolis.” Last modified April 13, 2025. https://ancient-greece.org/history/history-of-the-acropolis/.

The British Museum. “An Introduction to the Parthenon and its Sculptures.” Published January 11, 2018. https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/introduction-parthenon-and-its-sculptures.

The British Museum. “British Museum Collection.” Fact Sheet. Published 2019. https://www.britishmuseum.org/sites/default/files/2019-10/fact_sheet_bm_collection.pdf.

The British Museum. “Everything you ever wanted to know about the Rosetta Stone.” Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.britishmuseum.org/blog/everything-you-ever-wanted-know-about-rosetta-stone.

The British Museum. “History.” The British Museum Story. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/history.

The British Museum. “Moai.” Contested objects from the collection. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/moai.

The British Museum. “The Benin Bronzes.” Contested objects from the collection. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/benin-bronzes.

The British Museum. “The Parthenon Sculptures.” Contested objects from the collection. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://www.britishmuseum.org/about-us/british-museum-story/contested-objects-collection/parthenon-sculptures.

Gravenstein, Sophia, "Lost Art and Lost Lives: Nazi Art Looting and Art Restitution" (2022). Gettysburg College Student Publications. 982. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2063&context=student_scholarship.

Koukoumakas, Kostas and Seddon, Sean. “Parthenon Sculptures deal 'close', ex-Greek official says.” BBC. December 3, 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cy8y97x8xm0o.

Marshall, Alex. “British Museum Sues Former Curator for Return of Stolen Items.” The New York Times, March 28, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/27/arts/design/british-museum-thefts-peter-higgs.html.

The New York Times. “Greece to Ask Britain For the Elgin Marbles.” The New York Times, May 15, 1983. https://www.nytimes.com/1983/05/15/world/greece-to-ask-britain-for-the-elgin-marbles.html.

Rothfeld, Anne. “Nazi Looted Art: The Holocaust Records Preservation Project.” National Archives, Vol. 34, No. 2 (2002). https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2002/summer/nazi-looted-art-1.

Stephen, Lesie, Sir. Dictionary of National Biography. Vol 7. New York Macmillan, 1885-1900. https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofnati07stepuoft/page/130/mode/2up.

UK Parliament. Charities Act. 2022. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2022/6/contents.

UK Parliament. Holocaust (Return of Cultural Objects) Act. 2009. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2009/16/section/3.

UK Parliament. Human Tissue Act. 2004. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/30/section/47.

UK Parliament. British Museum Act. 1816. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Museum_Act_1816.

UK Parliament. British Museum Act. 1878. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/41-42/55/pdfs/ukpga_18780055_en.pdf.

UK Parliament. British Museum Act. 1902. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Edw7/2/12/pdfs/ukpga_19020012_en.pdf.

UK Parliament. British Museum Act. 1963. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1963/24/section/5/enacted.

UK Parliament. “Elgin Marbles.” Lord’s Chamber. December 14, 2023. https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/2023-12-14/debates/EF44031F-D514-4DEE-B109-BC56E433715B/ElginMarbles.

UNESCO World Heritage Convention. “Acropolis, Athens.” Accessed April 24, 2025. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/404/.